Field Trips by Ellin Beltz |

Ultimate Field Trip -- Hawai'i - The Big IslandSpring Break 2000 - by Ellin Beltz | ||

|---|---|---|

As part of Dr. Charles Shabica's Coastal Processes course at Northeastern Illinois University, we spent a fortnight on the Big Island of Hawai'i. Our group exactly filled one 15-man rental van, but only if the luggage was packed exactly and no one changed seats. The photos on this page were given me by my fellow travelers. | ||

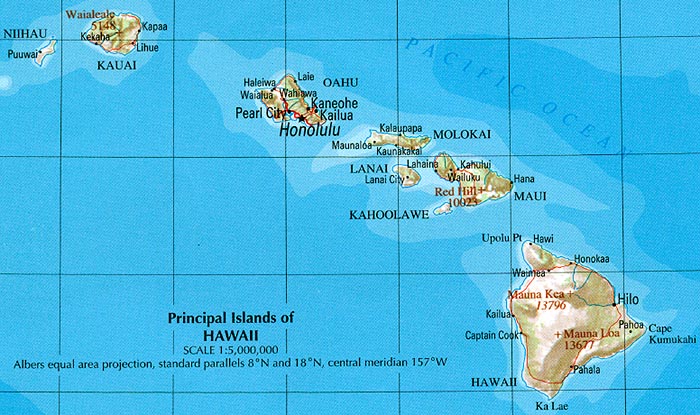

| The State of Hawai'i comprises not only the handful of familiar islands but a whole bunch of smaller islands, seamounts and submerged island guyots that extend in a bent string from the northwest Pacific Ocean down to the hot and active volcanos of the Big Island of Hawai'i. The state takes its name from the island which in turn was ruled by King Kamehameha ("Ka-may-ha-may-ha"), who prepared his state to voluntarily became part of the United States becoming our most accessible oceanic hot spot. |

Map of Hawaii

Courtesy USGS | |

| Hot spots are places on Earth's crust which overlay hot pools of molten magma which has risen directly from the mantle deep below the crust. They can surface either above ground, or underwater. In some cases, like Yellowstone National Park, the hot spot is melting and remelting the local rock along with receiving molten magma from below. Steaming fumaroles, fissures, smokers, rainbow pots, geysers and other geothermic vents release pressure, waste heat and steam from the sleeping dragon below. When the hot spot under Yellowstone blows - as it has blown before - it will be big and catastrophic for things living near and downwind from it. Continental hot spots tend to be dangerous when awakened; but for much of their history they lie buried and semidormant - inconceivable except to geologists. | ||

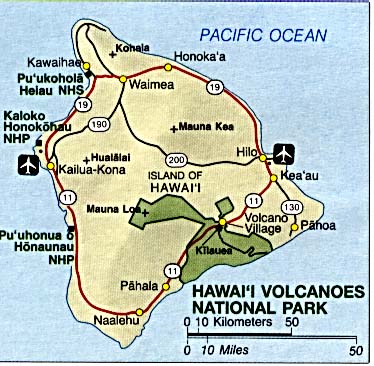

Map of the Big Island

Courtesy NPS | Not so the oceanic hot spot of the Big Island Hawai'i where hot steam rises, sulfide minerals precipitate, fissures smoke and lava flows just about each and every single day of the year. Several volcanos which make up Hawai'i. The island is in the shape of an arrowhead, with the points to the north and south, the tail to the west and the chipped point to the east. On the top of the arrowhead is the town of Kohala, buttressed to the north by an older, submerged cone. South of Kohala and slightly offset to the west is the volcano Hualalai. To the east, slightly closer to Kohala than Hualalai is Mauna Kea. This mountain slopes so gradually and is so omnipresent on the island that it takes a couple of days for the brain to register just how big it is. | |

| The top rises to 13,796 feet above sea level. It is argueably the tallest mountain on Earth if you count from the bottom of the ocean instead of sea level. It also has really nifty international astronomical observatory which are all the cool white domes you see way up at the top reflecting sunset's pink light. Various adventure companies will take you there in a jeep. Next time, maybe. We did go up Mauna Kea as far as the Onizuka Astronomy Complex and were treated to large telescope views of the planets Jupiter and Saturn, a dark nebula and several other fascinating outer space objects. It was really cold up there and hard to breathe, and it was hard to think if you weren't expecting the effects of altitude. Three of my students at NEIU were on the trip and we all noticed the altitude effects since we've been studying glaciers and mountains all semester. It still snows on Mauna Kea in winter, in addition to at least three previous glaciations; one of which is contemporary with our Wisconsinan ice advances here in Illinois. Next in elevation but larger by volume is Mauna Loa, topped by the NOAA weather observatory. This is the mountain you can see from Kilauea - the last surface active Hawai'ian volcano - where the USGS maintains a volcano observatory adjacent to the Jagger Museum on the rim of the crater. The edges of most of these volcanos have slumped off at various times and in all directions; many slides have ended up in the ocean. The newest hot spot volcano has not broken the surface of the ocean; it fumes and spews underwater offshore the southern coast. All these volcanos are laying over or have laid over the hot spot. Hawai'ian mythology and legend correlates perfectly with geological discoveries about the relative age of the string of craters which underlie the entire Hawai'ian chain. ... in the legends of Pele, the fiery Goddess of Volcanoes, Pele originally lived on Kauai. When her older sister Namakaokahai, the Goddess of the Sea, attacked her, Pele fled to the Island of Oahu. When she was forced by Namakaokahai to flee again, Pele moved southeast to Maui and finally to Hawaii, where she now lives in the Halemaumau Crater at the summit of Kilauea Volcano. The mythical flight of Pele from Kauai to Hawaii, which alludes to the eternal struggle between the growth of volcanic islands from eruptions and their later erosion by ocean waves, is consistent with geologic evidence obtained centuries later that clearly shows the islands becoming younger from northwest to southeast. [Source: United States Geological Survey Hawaiian Hot Spots page]Active volcanos play "ring around the rosy" of the actual magma pool; trading activity and venting different products - sometimes together and sometimes not. The confusing thing about Hawai'ian volcanology - and something I didn't understand until I was there - is that each and every single vent on each volcano has been given a name. So Haleuma'uma'u ("Ha-lee-mough-mough") is the big active crater inside Kilauea caldera which is itself the top of the Kilauea volcano (all pronounced "Kill-a-weigh-a"). This took me about three days to figure out because there's a whole chain of brain-twisting craters down the hillside and another one off to one side of the park called Pu'u O'o ("Poo-ooh Oh-oh "but say it fast) that was smoking hot and vents from which were spouting hot lava down the big landslide cliff called the "pali" and into the sea. We learned the two kinds of lava: ropy, billowy, high-temperature pahoehoe ("Pa-hoy-hoy") and low temperature, blocky, gas bubbled aa ("ah-ah"). Aa is named aa because you say "A-a" if you brush it or, worse, fall on it in which case you say something first and then "Ah-Ah!~!!!!" really loud. | ||

Lava samplers standing on pahoehoe with aa in background. Left to Right: Kevin Goldman, Lisa Trilli, Ellin Beltz, Johnathon Maynard, Nancy Stach. Photo by Rita Keefe. | Some of these craters just kind of fell down in the middle like the piston in a bike pump. Others were cracked by uprising magmas, earthquakes or landslides. In either case, hot lava emerges. It can erupt, trickle out, flow out by lava tube, be ejected by hot gases or water, splatter out like glass, spin out like hair, fly out like ash and blobs, curl up under surface tension into pendulous ropes, flow out like rocks on a glowing caterpillar tread, drop into water and instantly crystalize, flow out underwater and become the pillow lava of 101 texts, crystalize to new black sand to feed turtle beach or emerge in whatever way Madame Pele (the traditional goddess of magma whose latest home is inside Haleuma'uma'u) cares to make it so. After the eruptions, lava may remain like a lava lake, or it can drain out through tubes and end up miles away, like the flow which buried the traditional fishing village of Kalapana and its world renowned black sand beach. | |

| But I am telling you the story inside out. I should tell you that we landed first in Honolulu, took off again on an interisland hopper and landed in Hilo which is on the rainy east coast of Hawai'i. On our first day, some went up in a small plane to check out the flow from Pu'u O'o and get a GPS reading on where the lava was flowing while others walked/shopped Hilo and visited the Tsunami Museum which records and reminds the population of the dangers of ocean waves caused by earthquakes. The Hawaiian Islands receive many tsunami from earthquakes around Earth's "Ring of Fire," the Pacific Rim. |

Hilo after the devastating 1946 Tsunami.

Courtesy NOAA | |

The town of Hilo never rebuilt on tsunami land. As a consequence they have an ocean front drive on a breakfront. It felt rather like downtown Chicago - if Chicago were on the Pacific Ocean and had only 20,000 people! Residents were fishing from the road edge between the drive and the shore. And their cars were just pulled out on the lava blocks which lined the shoreline. Pretty soon we began to treat hard black lava as pretty indestructible too. Ferns and an Hawaiian plant called an Ohia are the first things to grow on the hard lava. Down by the ocean with the addition of salt spray, only a few hardy beachgrasses grow. And everywhere offshore are rocks. Tide pools galore. Some like the pools near Coconut Island within the town limits. But the runoff from the parking lot was flowing in the rain down the rocks to the sea and so these tide pools had only a few snails and a hopeful sponge spawning. We drove on. If you visit Hilo, try to stay at Arnott's. He's an Englishman of the old school and his gardens are abloom with many of the islands' most decorative native and introduced plants. We also saw more species of herps around his property per square meter than anywhere else on the island. He has a variety of rooms, all with a common under one roof dining hall and a tree house and a telly and book/board game lanai room which has to be seen to be believed. The only drawbacks are the timers in the bathrooms. Just a bit of Old Mother England there, 1066 and all that - turning off all the lights automatically and precisely in the middle of one's rather barbaric American showerbath. Take a waterproof flashlight - you'll need it anyway to catch geckos in the rain and have a shower by torch when the timer "mahalo for turning the lights off!" does its thing.Mahalo is supposed to mean "thank you." But it's usually used as a "duh" as in "mahalo for flushing the toilet." Also "aloha" is supposed to mean both "goodbye" and "hello" but the only people I heard actually say it were in Wal-Mart and Burger King so go figure. "Aloha, welcome to corporate American Company Name." Sounded forced. Maybe that's why the locals gave it up. Hilo reminded me of old Florida before the plastic mouse and its habitat covered the state. Hilo was bleached and salted and drenched by thunderstorms and shaded by palm trees and everything was a rather magnificent blue from reflected ocean light. Hilo is the also the flower capital of the island; we saw most of the flowers the guide book said occur on the rainy side here in the town rather than out in the bush. There's a statue of King Kamehameha here - at certain times it's draped in flower leis. It stands in the midst of a palm tree grove up a hill on the south end of town in a beautiful spot that feels similar to the great drive at Stanford or St. James' Park. | ||

Next we visited a small town at the intersection of a triangular roadway at the south east end of the island (the arrow's point).

Next we visited a small town at the intersection of a triangular roadway at the south east end of the island (the arrow's point). The road from Pahoa drops down lava flows, past Lava Tree State Park to the Kapoho Point with its incredible tidepools. New additions to my life list were probably everything I saw there. Notable were the sea cucumbers (both in and out of the water), several encrusting sponges and fish that look like they belong in the Shedd Aquarium, not swimming around loose where they could get hurt. Then I remembered that this is where they belong - not in some box at home - and started to swim around the various pools which make up the point. The tide was rushing in, so many bottom dwellers were becoming active. And these pools, like so much coast in Hawai'i is accessible with only a mask, snorkel and fins. | ||

Kevin and me snorkeling.

Photo by Johnathan Maynard. |

Even at relatively high tides (it was full moon) the deepest spots near shore were only about 20 feet. Most of the near shore area was shallow enough to stand up - but you were better off swimming (or corking as we came to call it) on the waves. Wave up - cork up; wave down - cork down. Much less strenuous than swimming and possible because the snorkel lets you breathe, relaxed with your head in the water. And - best of all - the mask lets you see. Flipper fins are nice, too. But make sure you practice putting them on and off before you get to the tide pools. Toads just make it look so easy. | |

| And we haven't even gotten to sunset of the second day. Hawai'i is like that. It has time, but is timeless. It has rain, but you forget. It has hot lava and we sampled it (which is a story to hear when you can see my slides - hot lava GLOWS). Hawaii Volcanos National Park is around the rim of Kilauea volcano which is most active right now. The active craters Halema'uma'u and Kilauea Iki are right along the rim as are the rift vents through which erupted hot lava and which were later overrun by hot lava from other eruptions. We saw steam and sulfur vents all around on Crater Rim drive and we drove down the Chain of Craters road to watch the hot lava flow down the slump cliffs (called "pali" by Hawai'ians). |

Ellin samples hot lava.

Photo by Lisa Trilli. | |

|

We met a wonderful NPS interpreter at the bottom of Chain of Craters Road. She noticed us because we were actually prepared for our lava walk (most of their visitors arrive expecting to be outfitted with GPS and On Star in their brains as well as never ending moveable shade and chilled water fountains on the hot lava). We observed parents carrying children who were not dressed and the whole group had no water, no food and no flashlights. Then they got gnarly at the other Parks guy for suggesting they stay back at the picnic table.

We actually came down the pali each one of the three nights; but with different parts of the group. One night it was much brighter than the others. Was Madame Pele mad at us for taking her substance hot from the vent. It would seem so. Our whole sampling area was consumed. And we had been there a scarce five hours before. Her baby lava - now one week and four days old - rests before me now. The next day we walked through a lava tube, found Pele's Tears and Hair and walked to see the floor of Kilauea Iki from above. Until I saw the people walking far below I was unaware of scale. They were as ants. And the whole thing had been filled with hot lava not so long ago. I could see why the locals were saying it was slow lava right now. Some of our group hiked to the top of Pu'u O'o through the rainforest and over the congealed aa, past kipuki - isolated forests in the lava flows - and to the top of the steaming crater itself. We have video of everything - it's wilder than MTV. | ||

Photo by Kevin Goldman | The day after that we went to the black sand beach about which the late Sean McKeown had sent me a clipping that showed a man right next to a teenager sized green sea turtle on the beach. The story read how the turtles were nesting here and NPS people had said they'd had 5,000 plus baby turtles launched this season. |

Photo by Kevin Goldman

|

| So we didn't really expect to see anything. But low and behold when we got to the beach there were two young teenager sized green sea turtles laying on the beach like beanie babies in a basket and crowds of people around them watching them take a nap. The locals said there were dozens more on the slow sloping boulder field which led down from the beach to the outer banks where the breakers were rolling. Swells and tiny breakers were rolling ashore, so in went the happy corks with mask, snorkel and flippers and wonder of wonders there we were amid about 40 green sea turtles. | ||

Photo by Susie Hayes.

| They were eating. As the swell lifted them up, they nibbled off the top of the rock. Swell down, turtle down, bottom of rock gets grazed. They hardly moved their flippers at all. Well, neither did we, but we were corking at the surface and they were in balance with the water and were floating, neutrally buoyant, just above the boulders.

My dive buddy and I taped a short underwater video of the feeding turtles and followed one which was swimming out to deeper water. Then he went in to dry off. | |

| I stayed in the water. It became a joke of the trip that my shirt from the Brigantine Stranding Center which reads "Marine Mammal" front and back was really my true name. Because my trip mates could never get me away from my new toys of fins, mask and snorkel in my old love, ocean swimming.

So, cold top fresh water layers or not, inrushing tides or not - I stayed in and watched and the turtles changed shift in the feeding zones. As the sea water came in, they moved in, but they seemed to be eating always off the rocks, not from the sand below. I didn't see anything that looked like grass or jellyfish - two items always cited on turtle menu. It seemed these turtles were eating algae encrusting the tumbled and polished lava boulders. Every so often, they would surface for air which they accomplished with a couple short flips to rise, open mouth gulp air, and immediately descend and begin feeding. About this point, I realized I'm in four feet of swelling sea water (not warm) surrounded by forty or so HUGE sea turtles (at least 2.5 feet apiece) each of which could if it wished turn me into hamburger and I never once wished for an On Star button. What I wished for was a video brain. So I could record the whole thing and show it to you. How beautiful was the light, shining through the water and dappling all with an ever changing light. How majestic were these turtles, hovering motionless in their garden, feeding eternally in this land of light and shade. How I never wanted to leave. How I realized you can get nitrogen narcosis in four feet of water if you forget to breathe. So I surfaced, like a turtle and grabbed some air, and when I put my face in the water a turtle came right up behind me and blew out an air bubble. Then he flipped away, his fins mere millimeters from my mask; his mind a mesozoic mystery of peace in a Pacific Ocean. Hawai'i is all about diversity. Sometimes you find your own there. | ||

Sunset at Kalapana. Photo by Nancy Stach | ||

Thanks to Charles, Eleanor and Anthony Shabica, Rita Keefe, Kevin Goldman, Nancy Stach, Johnathon Maynard, Lisa Trilli, Matt McBrien, Andrew Benzinger (this guy can drive anything over anything - we have video), Suzie Hayes, Teri Reviera, Arnold Nakamura and all the folks at NPS and USGS who made our visit so memorable. Thanks to the pilots, divers, captains, rentawizards, travel agents and all those without whom this trip would have never appened. And thanks to the turtles. Wow, what a trip.

| ||

Hawai'ian links |

| |

|

Return to my Homepage or email me Ellin Beltz / ebeltz@ebeltz.net

Updated January 10, 2008

| ||